In my spare time I take an historical interest in certain theories and ideas that I find to be more expansive, liberatory, and conducive to creativity than more narrow scientific or technical concepts. I relate this to William James’s distinction in The Varieties of Religious Experience between whether a particular idea is true, one the one hand, and what functions or meanings it has for a person on the other. While Jung’s psychological theory of types may not be accepted as the best empirical model for understanding personality, it can nonetheless be an interesting model for stretching how we think about how the mind works, and how we can conceptualize other people in everyday life.

So with that said, in this post I’d like to begin to lay out a description of some of Jung’s theory of personality. Jung’s theory of types underlies popular personality tests such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Keirsey Temperament Sorter. Despite the pervasiveness of some of Jung’s terminology—extraversion and introversion, sensing and intuitive types, perceiving and judging types, for example—I have found that his original ideas are frequently poorly understood and misrepresented.

Contemporary psychology and popular usage tend to define extraversion and introversion in terms of behavior or social aptitude: one is seen as extraverted if one is outgoing, energetic and interpersonally skilled, and introverted if one is shy, withdrawn, or socially awkward. The NEO-PI, for example, a popular instrument that measures the five-factor model of personality, defines extraversion with respect to “sociability, activity, and the tendency to experience positive emotions such as joy and pleasure.” Introverts are thus seen as “reserved and reticent.”

Unfortunately, this leads to some contorted understandings and confusions. I can’t count how many times someone has tried to make sense of the fact that they prefer to be alone or quiet, yet are socially fluent and outgoing when they need to be. We can easily see how the NEO-PI can be read as having a bias for extraverts and against introverts. Just based on the definition of the scale construct of extraversion, we can infer that introverts are construed as less happy, less energetic, and less socially capable than extraverts. Rather than two equal, opposite poles of personality, we get one dimension of preferable traits that extraverts have and introverts lack. This is, by the way, one of the reasons I appreciate Jung’s theory of types: he makes pains to consider different orientations to the world as equally valuable, and he makes a general, egalitarian observation and assumption that the types are evenly distributed “in all ranks of society…[s]ex makes no difference either” (p. 331; this and subsequent page numbers are from his volume Psychological Types).

Jung begins his “General Description of the Types” by distinguishing two types of people, defined by the direction of their interests. The two attitude types of extraversion and introversion concern whether a person has a predominantly outward- or inward-oriented approach to objects in the world. Jung used the word ‘object’ in contrast to ‘subject.’ Thus, an object could be an oak tree, a copy of the Picatrix, a housecat, a wine bottle, a person—anything existing outside the conscious subject, to be taken in by the senses and made sense of in thought.

To get at the two attitude types, Jung invites us to notice how “two people see the same object, but they never see it in such a way that the images they receive are identical… there often exists a radical difference, both in kind and in degree, in the psychic assimilation of the perceptual image” (p. 374)—that is, not in what is taken in, but how the object is taken up by the subject. “Whereas the extravert continually appeals to what comes to him from the object, the introvert relies principally on what the sense impression constellates in the subject” (p. 374). The extraverted type thus describes people whose “decisions and actions are [habitually] determined not by subjective views but by objective conditions” (p. 333). The extravert’s “interest and attention are direct to objective happenings, particularly those in his immediate environment” (p. 334).

So far, Jung’s view is not strongly differentiated from the popular, contemporary view. Jung considered introversion and extraversion two different ways of adapting to the world, and if it were merely the case that extraverts are adapted to the outer world and introverts not, then it would be easy to privilege the former over the latter. It is only in his conceptualization of introversion and what he calls the subjective factor that his major departure comes into view.

If it were merely the case that we took in data about the object, manipulated those data in whatever idiosyncratic way that we did—labeling it with a concept, judging it with a value, and so forth—then psychological functioning would simply be a matter of the fidelity of our conscious functioning to external reality. It is this perspective, Jung observes, that leads to “the epithet ‘merely subject’ [to be] brandished like a weapon over the head of anyone who is not boundlessly convinced of the absolute superiority of the object [in contrast to the subject]” (p. 375). Instead, Jung notes that a psychological fact—that is, an experience—consists of both an objective factor and a subjective factor, by which he means “that psychological action or reaction which merges with the effect produced by the object and so gives rise to a new psychic datum” (p. 375).

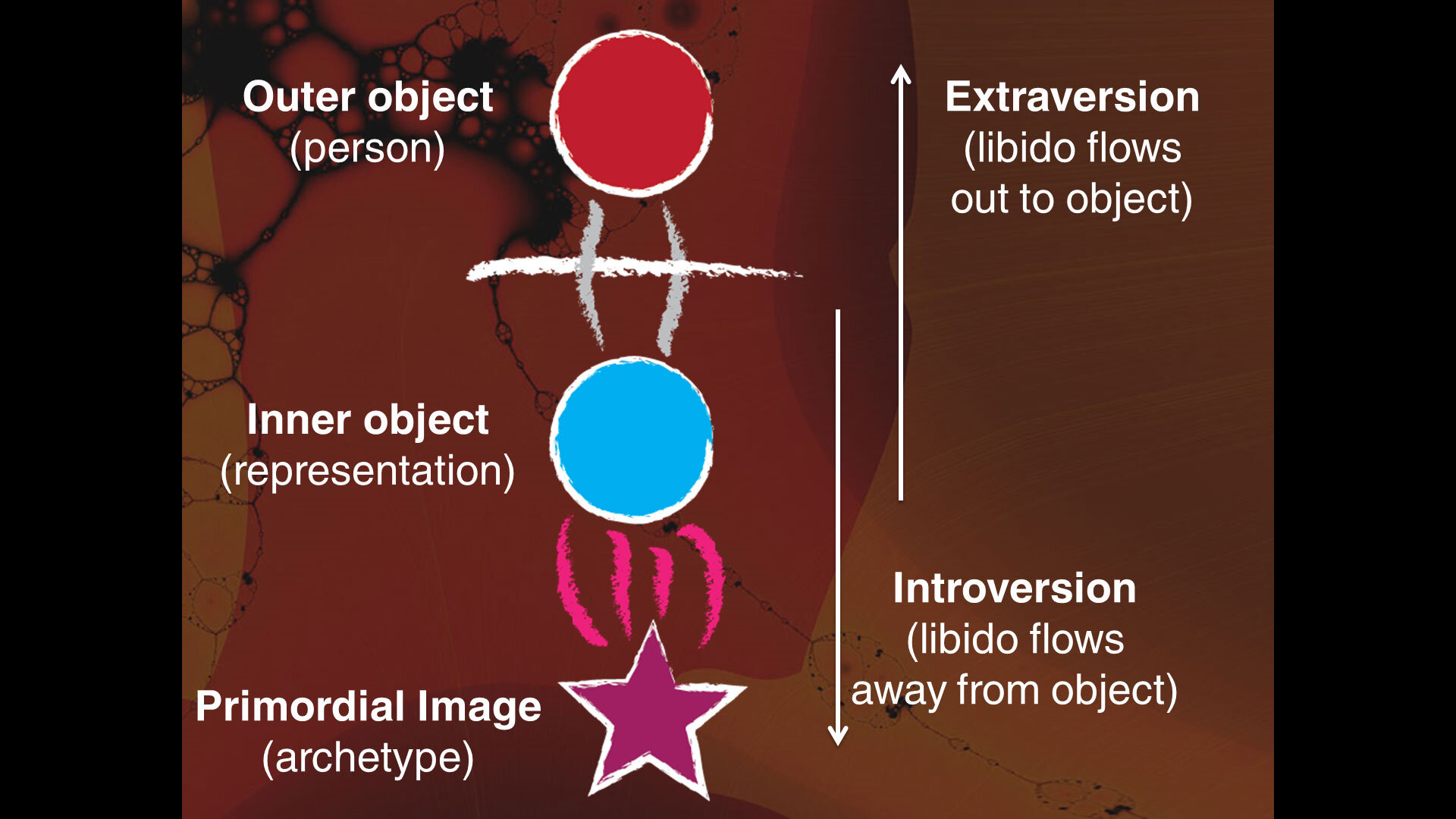

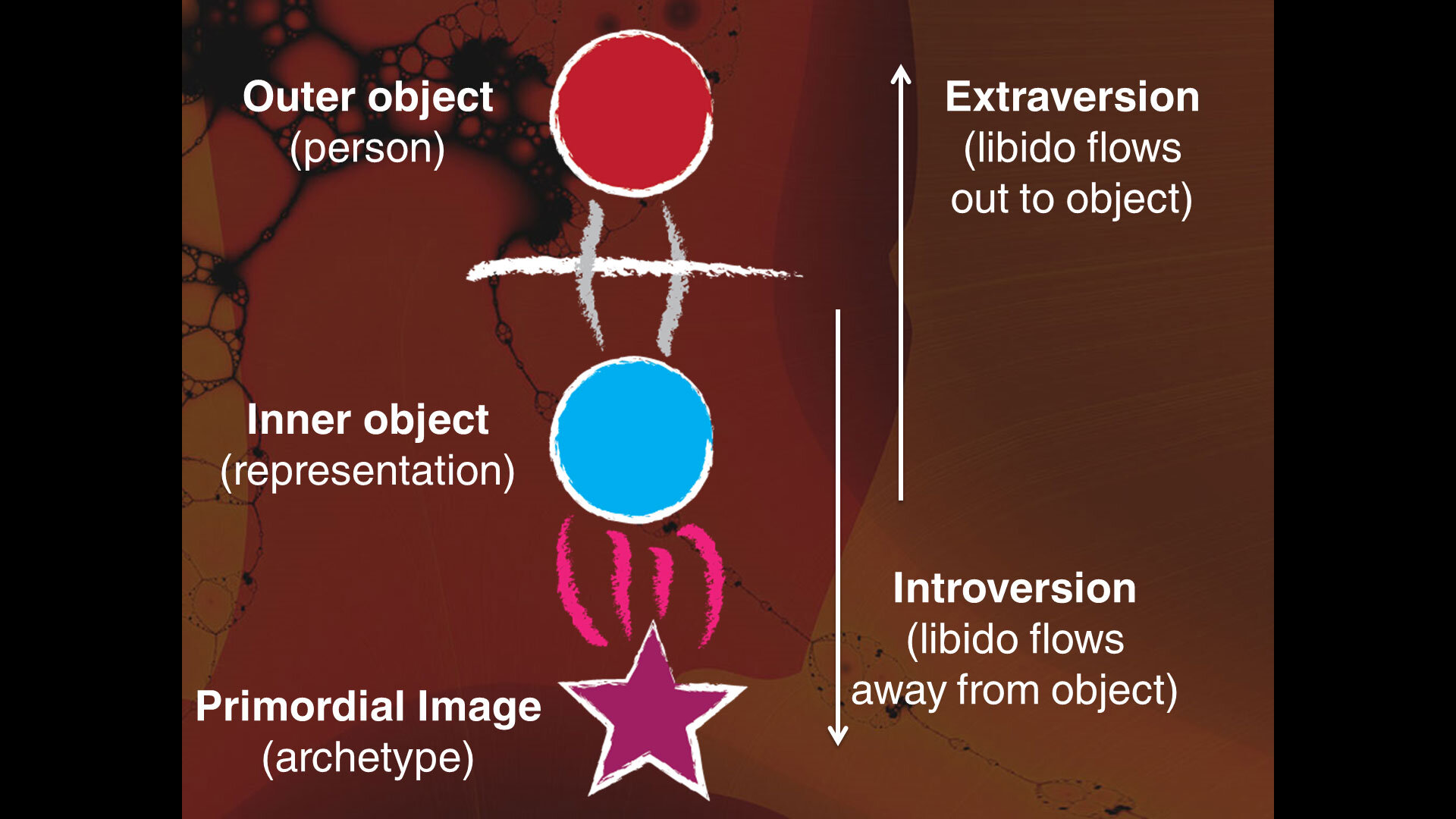

In a glossary postscript to his essay on the types, Jung offers a different conceptualization of extraversion and introversion in terms of the direction or flow not of interest or attention, but of libido. Jung used the term libido to refer not just to sexual energy, as Freud did, but to psychic energy more broadly: “the intensity of a psychic process, its psychological value” (pp. 37-38). Extraversion is “an outward-turning of libido…a positive movement of subjective interest towards the object” (p. 427), whereas introversion “means an inward-turning of libido… [such that i]nterest does not move toward the object but withdraws from it into the subject” (p. 452).

If libido, for the introvert, withdraws away from the object, where does it go toward in the subject? This is where Jung’s famous notions of the archetypes and the collective unconscious come in. He asserts that “the introverted attitude is normally oriented by the psychic structure, which is in principle hereditary and is inborn in the subject” (p. 376). To the extent that this “psychic structure” or subjective factor “has, from the earliest times and among all peoples, remained in large measure constant, elementary perceptions and cognitions being almost universally the same, it is a reality that is just as firmly established as the external object” (p. 375). This inherited psychic structure is what Jung means by the collective unconscious, or what he sometimes calls the objective psyche. Thus, in the same way that you and I, observing the same river, have equal access to its sensory qualities—the sound of its rushing, the light glinting off the surface, the breadth of the water and steepness of the banks, and so forth—so too do we each have equal access to its symbolic, archetypal potentials—analogies between flowing water and time, certain notions of sustenance and danger, separation of lands or worlds, and so forth.

What this implies is that to understand Jung’s theory of extraversion and introversion, we need a third term beyond object and subject: this third term is the archetype, or primordial image: “The primordial image is an inherited organization of psychic energy, an ingrained system, which not only gives expression to the energic process but facilitates its operation” (p. 447) Primordial images, or archetypes, appear in the psyche in veiled forms through symbols. Thus, a psychic datum, or experience, consists in the psychological act of uniting received objective data with the inborn archetypal images it constellates in our psychological structure. This psychological act results in a subjective experience, an inner object alloyed more or less by the fact of the external object or by its archetypal significance. Our attitude-type is described by our orientation to this action: whether our energy on balance flows more toward the object or the primordial image in this equation. The subject is the fulcrum on which this balance turns.

For Jung, a subject too oriented toward the object and away from the image is as one-sided and in need of compensatory balancing as a subject too oriented toward the image and away from external reality. Both external reality and psychic reality matter, both are collective, both inform and shape our experience, and each of us orients to them in characteristic ways.

Jung’s ideas about attitude-types were not where he ultimately stopped in his theory of personality, but rather his jumping off point. He observed that speaking of extraverted or introverted persons was merely an approximation, a description of someone’s overall, habitual leanings. To more deeply understand how he used the terms, we must note that he primarily used them not to refer to behavior or social fluency, nor even to overall trends in interest or attention, but rather to the characteristic operations of psychological functions: that is, the way we take in the world around us and organize it within our consciousness.

Jung divided psychic organization into four necessary, sufficient functions that allow us to make sense of the world. To understand any thing, we need to know that it is, what it is, what it is worth to us, and its horizons or possibilities. These correspond to the functions of sensing, thinking, feeling, and intuition, respective: two irrational or perceiving functions (sensing and intuition) and two rational or judging functions (thinking and feeling). Each of these functions can, in turn, be primarily organized in an extraverted or introverted direction: directed to a greater degree toward external reality or toward the archetypes.

I will define and explore the four functions and their operations in subsequent posts, but hopefully this gives you a better sense of Jung’s notions of extraversion and introversion. Rather than focus on outward actions, Jung was concerned with the most basic operations of the psyche: how energy flows, the ways we are active in perceiving and making sense of the world, and so on. Personality was therefore not a high-level averaging of our behavior, but rather a consequence of our fundamental way of being in and orienting to the world.

Read the next installment in this series here: Jung’s Function Types: 16 Ways of Being in the World.

References

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types (R. F. C. Hull, Trans. 2nd ed. Vol. VI). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pingback: Exploring the Different Types of Ambiverts - Simple Hermit

Pingback: Extraversion vs. Introversion: Where Do You Fall on the Spectrum? | Upfront Cortext

Comments are closed.